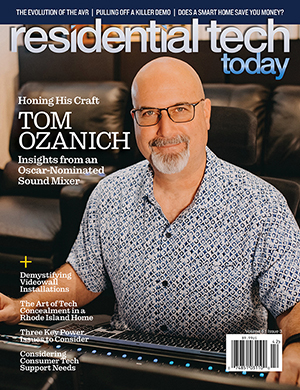

By Dennis Burger

Weather geeks in central Alabama don’t get our hopes up when we see a storm on the edge of the radar. We get our fair share of noteworthy weather systems, mind you, but the odds of any one rain shower making it halfway across the state without falling apart are generally not great. On the afternoon of June 28, 2018, though, local meteorological cognoscenti knew to take future radar seriously. There was a rare derecho headed our way – the sort of massive, widespread, long-lived gust front more common to the midwest and plains states.

Making this system doubly rare was the fact that it moved from northeast to southwest – perfectly contrary to the normal flow of weather in our region – consuming the entire state like the titular Blob from the schlocky 1958 B movie of the same name. It gobbled up the little community of Eclectic, to the northeast of Montgomery, at 3:54pm local time. It slammed into the northeastern suburbs of the capitol city at 4:25pm. It oozed its way into the downtown area, near the new National Memorial for Peace and Justice, at precisely 4:41. And at every stop along the way, it dropped rain at rates in the neighborhood of nine inches per hour, threw winds at the ground in excess of 30 miles per hour, and knocked temperatures down from the low-to-mid 90s into the upper 60s Fahrenheit in mere minutes.

Those details don’t come courtesy of some Rain Man-like memory for all things meteorological, or even official government data, but rather from to the logs of dozens of privately-owned personal weather stations scattered around central Alabama, nearly all of which collect temperature and rainfall data, many of which also constantly measure wind speed and direction, humidity, dewpoints, and other relevant information. Some even come equipped with live cams that point to whatever clear patch of sky there is to be found in the land of lumbering Loblolly pines.

Measure Locally, Upload Globally

Of course, Alabama isn’t unique in this respect. Weather Underground – one of the largest repositories of data collected from personal weather stations – draws information from more than 250,000 such sensor suites around the world, mostly concentrated in eastern Europe and the U.S. Even in the sparsely populated rangelands and prairies of Wyoming, you’d be hard-pressed to go much more than twenty miles in any direction without coming across a personal weather station logging its data to the Weather Underground PWS network on a regular basis.

But why? It’s not hard to understand the utility of avid weather watchers like Thomas Jefferson keeping meticulous meteorological diaries in the 18th century, but in an era where official weather measurements are available to anyone with a mobile phone, why do literally hundreds of thousands of private citizens band together to create a worldwide network of weather data? An Internet of Atmospheric Things, if you will?

For some it’s a matter of near necessity, especially for those who live in areas with microclimates, or in rural areas where professionally monitored FAA or National Weather Service weather stations are thin on the ground. If you’re a farmer or gardener who needs to keep track of daily, weekly, or monthly rainfall, after all, it’s probably of little consequence how much of it has fallen at your local airport or military base. What matters is your own hyperlocal weather conditions, and there’s no substitute for measuring them yourself.

Especially when you can use your own measurements to automate events in and around the home. You might, for example, interrupt your regular sprinkler schedule if rain has already fallen today, or up your watering schedule if a certain number of days has passed with no measurable precipitation.

With a robust enough smart home system, you can also have your thermostat settings adjust to the conditions outside your door, raise and lower shades, turn lights on or off, or anything else you might want to trigger based on the weather. Of course, you could also do much the same by relying on the outdoor temperature sensors that come with many thermostats and other such single-purpose devices. Which raises an interesting question:

What is a Personal Weather Station, Exactly?

The fact is that there’s no real hard definition of what counts as a PWS. Some units sold as weather stations, like the popular BloomSky, only collect temperature, humidity, barometric pressure, and rainfall rate data, although BloomSky does add a built-in webcam to the mix. You can add an additional sensor that measures wind and rainfall accumulation, as you can with the also-popular Netatmo, which focuses just as heavily on indoor air quality as it does outdoor conditions.

When most people say “personal weather station,” though, they’re probably thinking of all-in-one scientific sensor suites that generally range in price from $500 to $7,000, which gather weather data from a single multi-sensor chassis.

Those data are then transferred – either wired or wirelessly – to an indoor hub or console where they can be viewed, stored on a local computer or web portal, or – if supported – uploaded to web services like the aforementioned Weather Underground PWS network, along with other repositories like pwsweather.com and the über-nerdy Citizen Weather Observer Program. Some weather stations even go further by allowing you to add sensors for additional data, like leaf wetness, along with the temperature, moisture, and salinity of your soil.

Of course, “$500 to $7,000” is a pretty steep price range, which raises obvious questions about what, exactly, climbing that mountain of price gets you. It’s mostly a matter of durability and build quality, but in the case of the WeatherHawk 621, a PWS beloved amongst high-end home automation installers, you also get swanky features like built-in automatic heating to stave off freezing moisture in the winter and – perhaps most importantly – dedicated drivers for home automation systems like Control4, Crestron, Savant, Vantage, and AMX. That’s especially noteworthy given that high-end integration of most weather stations requires the use of generic drivers that rely on external APIs, typically from services like Weather Underground.

What to Consider Before Purchasing Your Weather Station

All of these variables mean that if you’re thinking of installing your own personal weather station, you first need to decide what, exactly, you want to measure and what you want to do with those measurements. When I spoke with Shaunna Donaher, senior lecturer at Emory University in the Department of Environmental Science, about the most important features people should look for, she had this to say: “I think temperature and humidity, wind speed and direction, and rainfall total are probably the most important.

Weather enthusiasts may also like rain rate, especially during intense downpours. Having indoor temperature and humidity on the display console or app is nice for the sake of comparison, but not required.” But most crucially, she says, “[It’s important to shop for a] personal weather station that is actually measuring the variables and not only pulling them in from nearby official reporting stations, because otherwise you could just look up those stations on your own.” She’s referring in this case to the glut of $40 to $50 “weather stations” available on Amazon and other e-tailers that simply act like the LCD wall-panel equivalent of the weather apps on your smartphone.

One other thing to consider if you’re planning on shopping for a weather station is where you’ll install it. Because location matters, especially if meteorological accuracy is what you’re looking for. According to Weather.gov’s guidelines for weather station siting, to get a proper temperature and humidity reading, your measurements should be taken 1.25 to 2 meters above a level patch of ground that isn’t covered with rocks, concrete, or dark surfaces, and at least two heights away from the nearest object (in other words, if your house is 15 feet tall, your temperature/humidity readings should be taken 30 feet away from the house). Proper wind readings, meanwhile, should be taken 10 meters above the ground at a horizontal distance of 10 times the height of the nearest object likely to obstruct wind flow.

If you read the above and thought, “There’s no way!” especially with a single multi-sensor unit, you’re onto something. Personal weather stations are almost never installed to such exacting specifications. Especially when you consider the fact that they often need to be placed with regular maintenance – cleaning, battery changes, etc. – in mind.

I spoke with Brian Peters – weather station enthusiast, former warning coordination meteorologist at the National Weather Service office in Birmingham, and current contributor to WeatherBrains, a popular netcast for Alabama weather geeks – about this, and he had the following perspective: “I know that my observations of wind will probably not be as accurate as [those of local professional weather stations]. And because of the trees on my property, I’m probably not getting as complete a mixing of the air, so my temperature observation may be off a trifle. But I knew about all of these limitations going into the installation of my weather station, so I did the best I could.”

Even proper placement is no guarantee of accurate measurements, though. I’ve been operating and maintaining four different weather stations on my own property for the better part of a year now, with most of them positioned within a few feet of one another, and their temperature measurements often differ by as much as four degrees Fahrenheit, largely owing to the fact that some are better shielded and ventilated than others. And although three of them are connected to Weather Underground’s PWS network, only one of them – a Davis Instruments Vantage Vue Wireless system – has passed the service’s quality control checks for data validity, sensor integrity, and reasonable agreement with local professional stations consistently enough to earn Gold Star status. But when it comes down to it, Peters says, “my station data are primarily for me, so I can live with them.”

In other words, the attitude of your average weather station operator and enthusiast is similar to that of Richard Feynam, who – when asked about the utility of theoretical physics – compared it to sex: “Sure, it may give some practical results, but that’s not why we do it.” To make that analogy slightly more relevant: yes, personal weather stations can in many cases be put to local use, tying in with smart home systems and triggering automated events like adjusting the thermostat or tweaking your irrigation schedule.

Yes, their data can be uploaded to the cloud and aggregated with the data from thousands of other such devices from around the world. And with some effort, you can collect data up to the standards of the National Weather Service. But in the end, that’s not really the point. The real appeal is probably best summed up by Donaher, who put it thusly: “Working with instruments that record weather variables helps bring the weather ‘indoors.’ It gives you a sense of the climate and the changes in climate trends. And perhaps more importantly, it gives you a sense of how those changes in climate can impact your day-to-day life.”

Feature Image: Davis Vantage Vue weather station