Seeking a Cinema Sommelier

Financial Times publishes the e-zine “How to Spend It,” which is heady reading for those who have “it” to spend and a good place to be seen for those who create items worthy of consideration. The publication features everything from articles on A-list homes, their architects, and designers; to cars, boats, and planes; to watches, wine, fashion and more. It’s a true benchmark of luxury where those who appreciate the finer things in life can learn more about favorite pursuits.

One such pursuit is the acquisition and enjoyment of art, which is quite prevalent. Paintings, sculpture, and works of many genres make up an art connoisseur’s private collection. Those who do curate collections of admired works often augment their passion with home makeovers – including private galleries – to better share and enjoy them. One artform, however, is notable for its absence. Moviemaking.

“Moviemaking is the most complete, truly contemporary art form. It brings narrative, acting, scenery, lighting, sound, and music together into the most marvelous machine for emotion.”

– Renzo Piano, Architect, Academy Museum of Motion Pictures

But how does one curate a private collection of this artform? Whereas sculpture, even substantial works, can be ensconced in a purpose-built gallery or display, private or otherwise, and other, more conventional artforms can easily and favorably be exhibited. Film, with its singular depth of brilliance and significance has as unique a set of challenges. Film’s artistic value is in its effect on the individual – those moments when tears, laughter, memories, or thrill arrive without warning. Billions are invested in other artforms that never evoke such quintessence and memorable reaction. But how can this unique genre be collected?

It is an important question because film is likely to change dramatically and not necessarily for the better. It already has.

These days, economics and technology have combined to compromise film in varying ways. A new definition for the term “theatricality” (referring to whether or not a film is likely to fill seats) is a result of theater economics. As a result, many of the most artistic works do not enjoy a long theatrical run. Why? Because the audience will wait to see these less “theatrical” films in their living rooms, or worse, on their phones! This is where technology, which in many ways has created even greater potential for the artform, has created an everyday container that serves to diminish the experience for much of the population. Anyone who has stood in the presence of a painting masterpiece, such as a Raphael, da Vinci, or Monet, knows that an image on a flat portable screen cannot communicate the true cinematic experience.

This also has potential to affect the creators of the art. If Lawrence of Arabia were being produced today, the iconic desert scene would not exist. It would not have worked on living room televisions and portable phones. The imagery was too grand to be realized on such devices. When considering all the tools available to modern filmmakers, cinema graphic, sonic, immersion, special effects, one realizes that to properly experience this artform requires a powerful delivery system and specialized environment. How will the artists respond to the knowledge that their work will only be seen on compromised delivery systems? Will they compromise accordingly? What creative potential, even today, is being lost? What other form of art suffers such degradation?

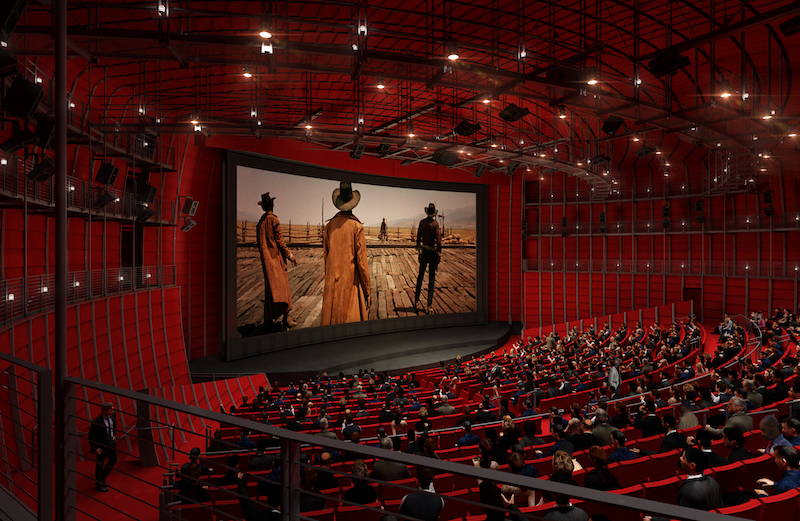

It is not all bad news. The same era of technological development that produces ubiquitous flat panel displays and a population mesmerized by hand-held screens has yielded some very powerful tools for the artists of the film industry. Film directors speak of the “big window” that is the cinematic screen. Digital video technology provides cinematographers the ability to produce big windows to film’s fantasy world that are astonishingly good. Immersive sound formats create soundscapes so convincing that what was once the filmmaker’s goal of evoking a willing suspension of disbelief, has become a phenomenon where audiences are drawn into the experience inexorably.

Unfortunately, the state of the audience remains compromised. Even those blockbusters that pass the theatricality test are displayed in commercial cinemas that leave much to be desired. Those who choose to watch movies on handheld devices or typically compromised home AV systems do not realize what they are missing. The film lover may never experience the work of the artist as it was intended to be experienced. If this trend persists, what will the effect be on the art?

A very real alternative exists, and there is precedence. In the fine art world, private collections are a significant trend. In fact, record breaking acquisitions have made quite a stir. What is relevant to our conversation, however, is the underlying motivation of many private art collectors. Namely, their love for and desire to preserve the art. To that end, fine art lovers not only acquire art but invest in private facilities to optimally shelter, display and enjoy their collections. This is not an anomaly. See www.glenstone.org/about/mission or visit www.artnews.com/art-collectors/top-200-profiles/ and it will be clear that many are actively collecting art and building galleries in their homes. Art Connoisseurship is alive and well!

For film, the private gallery is the private cinema. It is possible now to commission a private cinema that will preserve the artform similarly to the private art facilities mentioned above. The goal is building a facility that will present the art as it was intended, rather than how it is commonly experienced today, in tawdry “cardboard-box” multiplexes, home renditions of the same, or worse, personal devices. These rooms are performance-engineered and artfully designed to embody the substance of theaters of note, in fact, often turning out as superior to most commercial cinemas.

Cinema is primed for connoisseurship. A vast reserve of work exists, and the state of the art holds promise for even greater expression. And, like fine art, there is concern for the preservation of the artform. What is missing is the community.

Fine art enjoys a community of enthusiasts who interact and raise awareness and excitement. This community includes professional art consultants, of course, but more common are the art enthusiasts themselves. For cinema, the knowledge of how good it can be, the connoisseurship if you will, has remained in the realm of the professionals. If the artform is to thrive and a community of cinema connoisseurs are to emerge, a catalyst is needed. Could that catalyst be analogous to the sommelier for fine wine? A cinema sommelier?

Cinema sommeliers will be enthusiasts in their own right – “cinema connoisseurs” in the truest sense. I’m talking about a community of professionals and devotees who, like art consultants, gallery designers, and art lovers in the fine art world, have facilitated the emergence of private galleries and helped curate private collections in their goal to preserve their art. Professionals will guide a growing community of cinema connoisseurs, not from a profit incentive but from pure passion. The business side of this will take care of itself as it has in the case of fine art consultants mentioned above. Word will get out.

The ability to experience “the most complete, truly contemporary art form” in one’s home with those we love, as it was intended to be experienced, while playing a part in the preservation of that art, is a compelling, singular opportunity.